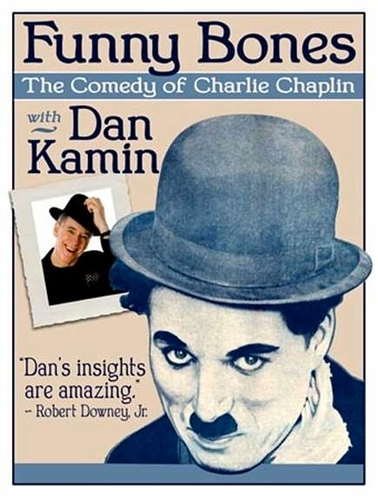

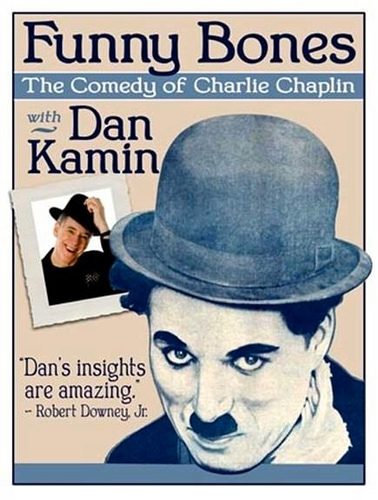

In honor of the 100th anniversary of Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Little Tramp,’ Flicker Alley sat down with Chaplin expert Dan Kamin, the man who taught Robert Downey, Jr. how to promenade and pratfall in the Oscar-nominated film Chaplin (1992). In Part 2 of our two-part interview, Kamin discusses the evolution of ‘the Tramp’ from Keystone Studios to The Great Dictator and Chaplin’s role in early romantic comedy.

In honor of the 100th anniversary of Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Little Tramp,’ Flicker Alley sat down with Chaplin expert Dan Kamin, the man who taught Robert Downey, Jr. how to promenade and pratfall in the Oscar-nominated film Chaplin (1992). In Part 2 of our two-part interview, Kamin discusses the evolution of ‘the Tramp’ from Keystone Studios to The Great Dictator and Chaplin’s role in early romantic comedy.

How do you feel ‘the Tramp’ evolved from Chaplin’s Keystone days to THE GREAT DICTATOR?

In the Keystone films he’s an amoral scamp, outrageously flirtatious with women and prone to violence with men. The following year Chaplin hired the beautiful Edna Purviance as his leading lady, and he introduces a new element of romance to his films. Her presence inspired Chaplin to soften the character’s rowdier behavior. The Tramp develops a conscience and a soul, and occasionally suffers heartbreak.

Chaplin began experimenting with how to incorporate serious material into a comedy as far back as the 1914 Keystone film The New Janitor, in which he plays a downtrodden soul who eventually thwarts a robbery. In 1918 he released Shoulder Arms, a landmark comedy in which the Tramp puts his comic spin on the horrors of trench warfare. Because the film came out while the war was still raging, Chaplin released it with considerable trepidation, but it became his biggest hit up to that time. It confirmed his reputation as not only the funniest man in the world, but as a major artist who had earned the right to to comment on world events through his art.

He took that responsibility seriously. In addition to the comedy and romance that the public had come to expect in his films, he used the character as a means to showcase societal problems such as poverty (The Kid), greed (The Gold Rush), urban despair in the midst of affluence (City Lights), the inhumane factory system and the Depression (Modern Times), and even the rise of fascism (The Great Dictator).

The Great Dictator came out in 1940, a full year before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Capitalizing on the bizarre resemblance between the Tramp and Hitler, Chaplin played a double role, savagely lampooning Hitler as a preening buffoon, while portraying the Tramp as a hapless Jewish barber victimized by the dictator. Like Modern Times, this was pulled right from the headlines, and Chaplin had to race against world events to complete it before Hitler became too ominous a subject for comedy. The film was a tremendous if controversial hit, causing riots in some South American countries and banned in the nations of Europe that had already fallen to the Nazis.

At the end of the film the shy, inarticulate Tramp switches places with the dictator, and he must speak to the assembled troops following their brutal invasion of a neighboring country. The Tramp grows impassioned as he delivers a fervent plea for humanity over insanity, but as he speaks he seems to become a different character, someone who makes his point with words rather than action. With this speech the Tramp disappears before our eyes, never to be seen again. In effect, Chaplin sacrifices his great character for his great cause.

With Chaplin, props became more than just props; they became alive and they become inexorably linked with his character. What can ‘the Tramp’ teach us about working with props?

Almost every prop Chaplin touches turns into something else before our eyes. Transforming things was one of Chaplin’s greatest gifts as a comedian. When he spears those bread rolls and makes them dance, we see the forks as legs and the rolls as feet. It’s a visual pun. It’s only later that it might occur to us that Charlie has conjured a puppet replica of himself, with his expressive, oversized face hovering over his spindly fork-legs and the oversized roll-feet. His films seethe with such inventive business, and the gags work so well because they’re always grounded in the dramatic action—he’s always doing these things to get out of some kind of jam.

Chaplin’s ability to create visual puns is at the heart of his cinematic achievement. Think of almost any memorable Chaplin sequence and you’ll find a visual pun at the heart of it.

Love, in its many forms, plays an integral role in most of Chaplin’s work. How do you think the idea of love relates to comedic performance?

Although he seldom gets credit for it, Chaplin was a pioneer of romantic comedy. From 1915 through 1923 he made 35 films with Edna Purviance, and we watch them meeting and falling in love over and over again. It’s a glorious catalogue of flirtation and courtship, and sometimes she breaks his heart at well.

Chaplin himself wrote about how difficult it was to motivate a believable romantic relationship for the Tramp, given the character’s position at the bottom of the social ladder. Other clown-comedians, such as Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, and the Three Stooges, didn’t even try. Romantic love plots were reserved for dramatic actors and light comedians such as today’s rom-com stars.

Chaplin made it work, because as his films grew darker and more realistic his character’s humanity deepened. He is totally believable as the adoptive father of Jackie Coogan in The Kid, and a convincingly lovelorn suitor in The Circus and The Gold Rush.

And City Lights, arguably the greatest romantic comedy ever made, is a meditation on the nature of love itself, with an ending that critic James Agee called “the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.” Few would disagree.

What’s your favorite Chaplin film?

A Dog’s Life.

What’s the future for the ‘Little Tramp’? Will he live on for another hundred years? If so, why?

It’s been a hundred years so far and we’re still laughing. There’s no reason to think we won’t be laughing a hundred years from now, or a thousand. I sincerely hope so, because if we’re not I’ll have to write another damn book.

Dan Kamin trained Robert Downey, Jr. for his Oscar-nominated performance in Chaplin and choreographed the film’s principal comedy sequences. He also created the physical comedy sequences for Benny and Joon with Johnny Depp. The author of two books on Chaplin, he is a well-known comedian and mime in his own right, performing worldwide in theatres and with symphony orchestras. See Dan in action at www.dankamin.com.

Check the Flicker Alley blog, The Archives, to catch up with Part 1 of our interview with Dan! You can see the debut of the ‘Little Tramp’ in Kid Auto Races at Venice, part of our CHAPLIN AT KEYSTONE 4-Disc DVD collection.