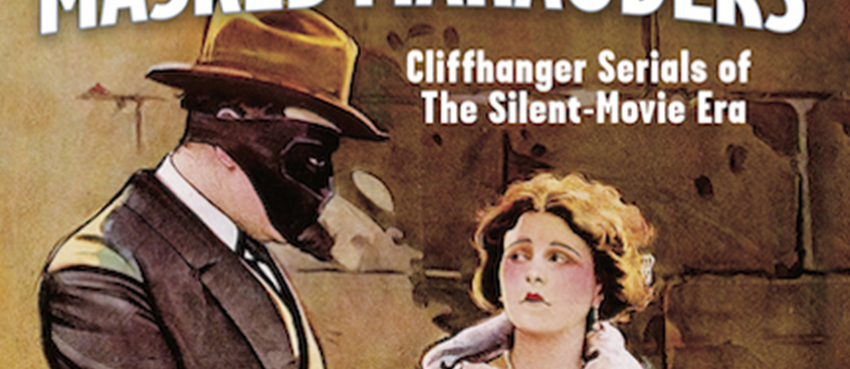

In this exclusive essay for The Archives blog, Ed Hulse, serial film aficionado and author of Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders: Cliffhanger Serials of the Silent-Movie Era, takes us on a journey through the genesis of American serial film, its lasting contributions to the film industry, and how it compares to its European counterparts, such as the French silent serial, THE HOUSE OF MYSTERY.

The basic elements of film grammar were already well established by 1913, when the initial episode of The Adventures of Kathlyn—the first true “chapter play”—flashed upon theater screens. Nonetheless, the serial’s contribution to the film industry’s development has been habitually underestimated by critics and historians.

The basic elements of film grammar were already well established by 1913, when the initial episode of The Adventures of Kathlyn—the first true “chapter play”—flashed upon theater screens. Nonetheless, the serial’s contribution to the film industry’s development has been habitually underestimated by critics and historians.

Popular screen stars who made early appearances in silent-era serials included Jean Arthur, Lionel Barrymore, Wallace Beery, Constance Bennett, Lon Chaney, Boris Karloff, Laura La Plante, Adolphe Menjou, Warner Oland, Esther Ralston, Milton Sills, Rudolph Valentino, Warren William, and Anna May Wong. Broadway favorites Billie Burke, Irene Castle, and Lillian Lorraine each top-lined a chapter play, as did champion prizefighters Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, and “Gentleman Jim” Corbett.

James Cruze and Irving Cummings acted in early serials before wielding megaphones from behind the camera, where they achieved greater fame. Journeyman directors W. S. Van Dyke, George Marshall, Richard Thorpe, and George B. Seitz enjoyed lengthy stints with major studios after helming episodic thrillers for Pathé and Mascot. Oscar-winning cinematographers Joseph August, Stanley Cortez, Linwood Dunn, Arthur Miller, and Leon Shamroy cranked cameras on serials before graduating to big-budget feature films. Playwright Philip Barry, whose Broadway hits included Holiday, The Animal Kingdom, and The Philadelphia Story, temporarily abandoned stage work in 1924 to write a Pathé serial, Ten Scars Make a Man.

Notwithstanding the eventual prominence of the people named above, the chapter play’s importance in American film history cannot be attributed to the careers it helped launch. The serial had much broader impact than it has been credited with. It changed the way motion pictures were advertised and distributed. (Distributors of episodic thrillers pioneered the use of billboard advertising and the practice of saturation booking known as “opening wide.”) It codified narrative devices still employed today in movies and TV series, among them the so-called “cliffhanger” ending. And it made weekly theater attendance a habit for millions of Americans, thus facilitating the industry’s rapid growth during the silent era.

The motion-picture serial was strictly a child of commerce, born not to advance the art of narrative filmmaking but, rather, as a cross-promotional device aimed at increasing the circulations of magazines and newspapers. There was nothing new about the idea; it had been bruited about in 1907. But five years passed before someone implemented it. The Edison Company in 1912 experimented with a loosely connected series of one-reel dramas, released monthly to correspond with the publication of prose versions in the McClure magazine Ladies’ World. The success of What Happened to Mary? inspired another circulation-building stunt, this one originating in the minds of Chicago Tribune editor Walter Howey and circulation manager Max Annenberg, who forged an alliance with local filmmaker Colonel William N. Selig. The Colonel agreed to produce a sequential film whose chapters would be adapted to prose and not only serialized in the pages of the Tribune but syndicated to other papers as well. Fictionalized by Harold MacGrath from scenarios by Gilson Willets, The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913) was phenomenally successful. It had a reasonably complex plot, a strong central villain, and endings that interrupted thrilling action sequences before their conclusion, leaving viewers in what was called “holdover suspense.”

From its beginnings, the motion-picture serial reflected the influences of popular-priced stage melodrama and mass-market fiction, the latter delivered to thrill-hungry readers in cheaply produced woodpulp magazines. Chapter-play writers hewed closely to the well-established conventions of pulp fiction and sensation-based theatrical productions because they hoped to attract the same consumers to which those mediums appealed: largely working class, with a small but significant percentage of the middle class; urban dwellers and small-town residents alike. The relatively short lengths and primitive storytelling techniques of early motion pictures made inevitable a reliance on melodrama, with its direct narratives, broadly sketched situations, and clearly defined character types.

Stage melodrama emerged at the turn of the 19th century, but it took nearly a hundred years to evolve into the form from which early filmmakers drew plots, themes, and concepts. By then known as “10-20-30” (reflecting the prices charged by theaters specializing in this type of show), the thrill-charged melodrama flourished in small towns and big cities alike, playing mostly to uncritical, marginally literate spectators. The hallmark of 10-20-30 was sensationalism.

The average 10-20-30 story was presented in four acts and incorporated as many as 20 separate scenes, some ending with thrilling situations—not unlike the serial’s “cliffhanger” endings—calling for elaborate scenic effects. The climax of Joseph Arthur’s The Still Alarm (1890), adapted to celluloid several times during the silent-movie era, boasted a race-to-the-rescue climax in which real horses, hitched to a real fire engine, galloped on a treadmill (backed by a revolving cyclorama to create the illusion of speed) to the scene of a conflagration represented by smoke wafting across the stage from carefully hidden pots.

The heroine of Charles T. Dazey’s In Old Kentucky (1893), which also had several screen incarnations, was called upon to swing by rope across a deep chasm and rescue a racehorse from a burning stable. Ramsey Morris’s The Ninety and Nine (1902) depicted the passing of a locomotive through a forest fire, and Charles A. Tyler’s Through Fire and Water simulated the plunging of a canoe over a waterfall. Such effects required complicated sets and apparatus, and were often achieved with astonishing verisimilitude. Both natural and unnatural disasters paraded nightly across the stages of 10-20-30 theaters.

The fiction in dime novels and pulp magazines naturally lacked the sensory appeal of the sensational stage melodrama, but it offered a level of narrative complexity rarely found in 10-20-30 theatrical fare. A popular setting was the mansion of mystery, where large groups of people assembled, one at a time, to pursue some sinister objective. There was also an emphasis on crime stories that routinely featured mystery men—some masked and cloaked, some grotesquely disguised—on both sides of the law. They clashed over treasure maps, hidden fortunes, secret formulas, revolutionary inventions, and deeds to valuable properties.

Early chapter plays often had urban backgrounds, reflecting not only a thematic predisposition but also the east-coast locations in which early production companies had studios: Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey’s Fort Lee and Jersey City. Thanhouser’s The Million Dollar Mystery and Pathé’s The Exploits of Elaine, both 1914 releases, were seminal serials built around master criminals with immense organizations. Malefactors plotted their depredations in secluded lairs outfitted with hidden doors, secret passages, underground tunnels, and basement torture chambers.

The American movie serial quickly stultified, a prisoner of its own clichés and inhibited by self-imposed restrictions on chapter length, subject matter, and budgetary expenditure. Chapter plays made in Europe, while similarly obsessed with crime and melodrama, were not as rigidly formatted, nor did they rely so much on physical action and breathtaking stunts to hold spectator interest. Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas, Les Vampires, and Judex are generally considered to be the most noteworthy examples of French serials, but the form was extremely popular in that country and dozens of as-yet-unheralded chapter plays were made there during the silent era. The 10 episodes of La Maison du Mystère (The House of Mystery, 1923), directed by Alexandre Volkoff and starring distinguished Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine, consume seven hours and unfold over an 18-year span. It incorporates into a mature and complex plot such familiar serial elements as murder, blackmail, and an innocent man’s efforts to clear his name. But the characters are more fully developed than is usually the case in American silent serials, and the narrative never devolves into a tiresome progression of chases, fights, captures, and escapes.

The American movie serial quickly stultified, a prisoner of its own clichés and inhibited by self-imposed restrictions on chapter length, subject matter, and budgetary expenditure. Chapter plays made in Europe, while similarly obsessed with crime and melodrama, were not as rigidly formatted, nor did they rely so much on physical action and breathtaking stunts to hold spectator interest. Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas, Les Vampires, and Judex are generally considered to be the most noteworthy examples of French serials, but the form was extremely popular in that country and dozens of as-yet-unheralded chapter plays were made there during the silent era. The 10 episodes of La Maison du Mystère (The House of Mystery, 1923), directed by Alexandre Volkoff and starring distinguished Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine, consume seven hours and unfold over an 18-year span. It incorporates into a mature and complex plot such familiar serial elements as murder, blackmail, and an innocent man’s efforts to clear his name. But the characters are more fully developed than is usually the case in American silent serials, and the narrative never devolves into a tiresome progression of chases, fights, captures, and escapes.

In short, it is everything the American chapter play might have been, had commercial considerations been sublimated to artistic expression.