Napoleon, Kevin Brownlow, and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival have been prominent on the cultural radar during the last few weeks, from features in the NYTimes and Wall Street Journal to countless blog posts [The Daily Mirror; Smithsonian’s Reel Culture] and mentions on Twitter [check out feeds from @SilentRobert; @LB_Society; @silenttoronto], and for very good reason. Kevin Brownlow’s latest and most complete restoration of Abel Gance’s 1926 film Napoleon will be playing four times (March 24, 25, 31 and April 1) presented by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. The epic 5 1/2 hour film will be presented with a musical score by Carl Davis, performed live by the Oakland East Bay Symphony at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California. These presentations are being lauded as ‘a once in a lifetime cinematic event.’

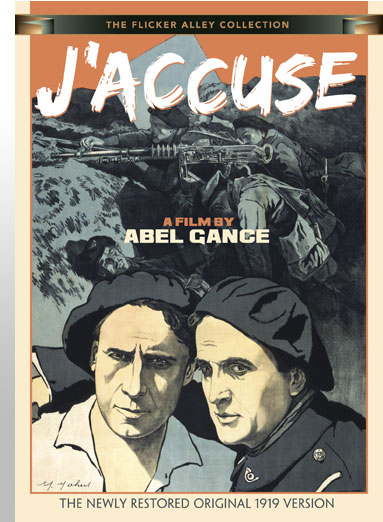

The team here at Flicker Alley is based in Los Angeles, so we’re lucky that we only have to drive about 6 1/2 hours or fly for less than an hour to get to Oakland! We’re trying to contain our excitement and not gloat too much because this week Silent London reminded us that not everyone, of course, will be able to attend one of the performances. In their wonderful (and very consoling) blog post entitled “How to beat the Napoleon blues,” Silent London lists five alternative ways of celebrating the legacy of Abel Gance. Number 4 on their list is to beef up on Gance’s filmography and watch his earlier films, J’Accuse (1919) and La Roue (1922) – both available on DVD from Flicker Alley! Both titles are also available for streaming through one of our digital distribution partners, Fandor. Additionally, La Roue will be airing on TCM on Sunday March 25, and J’Accuse aired last Sunday.

Filming “J’Accuse” on location. From left to right: Marc Bujard, Maurice Forster, Antonin Nalpes, and Abel Gance

We think this suggestion is not only good for those who are beating the blues, but also for those who want to get pumped even more before making it to one of the screenings. In watching these two earlier works, viewers will be able to trace Gance’s thematic and stylistic characteristics that come full-circle in his masterpiece Napoleon. For example, the virtuoso, rapid cutting famous in Napoleon can be directly traced through J’Accuse and La Roue. In the booklet essay “Waste of War” published in Flicker Alley’s release of the J’Accuse, Kevin Brownlow writes:

“Viewing J’Accuse again, I can see that Gance had not quite perfected his technique. The first half of the film is edited rather awkwardly – not helped by frequent pos-cuts (damaged film repaired in an arbitrary fashion which tends to look like a bad cut). But, in the second and third parts, he reveals some of the mastery he would display in La Roue and Napoléon. It is exciting to chart the progress of genius taking place before your eyes.”

Brownlow goes on to say that even though J’Accuse is not as masterful as his later work, it was technically and rhetorically more advanced than any other French film in 1919.

After the success of J’Accuse, Gance spent three years making his next epic: La Roue, the story of a locomotive engineer who saves Norma, an infant girl, from a train wreck and raises her as his adopted daughter. Like Napoleon, both La Roue and J’Accuse became sourcebooks for cinematic invention. Flicker Alley’s publication of La Roue features an essay by film historian William M. Drew, in which he describes how Gance’s use of rapid montage influenced scores of silent filmmakers including Clair, l’Herbier, Epstein, Dulac, Bernard, Feyder, Duvivier, Renoir. Gance’s editing style even had influence beyond the silent era. Drew writes:

“The rhythmic editing of La Roue shaped Renoir’s La Bête humaine, a 1938 film about railway workers. In the 1950s, François Truffaut and other directors of the nouvelle vague developed their approaches to cinema through exposure to the revivals of silent films, including those of Abel Gance, at the Cinemathèque Française.”

La Roue, much like Napoleon, is a lengthy film – clocking in at 4 1/2 hours. The full version of La Roue was first exhibited at the Gaumont-Palace in 1922 and then throughout France in 1923. When it came to showing the film outside of France, distributors requested a shorter version that could be shown in a single screening. Gance obliged them in 1924 by cutting La Roue from 32 to 12 reels, and it traveled the world in this truncated form. However, Gance had no control in the English-speaking world. In 1925, British distributors slashed La Roue down to 7, 500 feet – 7 0r 8 reels. Much of the film’s power was lost, and even the hero’s final death scene was omitted. Thus, British critics and audiences were not so enthusiastic about the film. According to Drew, this resulting crticial disaster perhaps explains why it never reached theaters in the United States. Napoleon faced similiar ‘shreddings.’ MGM drastically cut Napoleon in 1928 for its American release.

Thanks to the dedication of historians, archivists, and cinephiles J’Accuse, La Roue, and Napoleon are now reaching audiences, either on the big screen or on home video, in ways that emulate their original presentations and respect the artistry of Abel Gance.

For those of you attending one (or more) of these four historic performances, we wish you safe travels and enjoy the Polyvision! And for those who are unable to make the trek, we hope you can celebrate Abel Gance in your own way and take solace in knowing that in 2012 a silent film is the hottest ticket in the world!